DU – das Kulturmagazin: Icons of the Côte d'Azur by Edward Quinn

The October 2024 issue 930 of the renowned Swiss cultural magazine “Du” was dedicated entirely to Edward Quinn. You can find all the texts here.

Editorial: The most beautiful stage in the world

Oliver Prange, Editor-in-chief Du Magazine

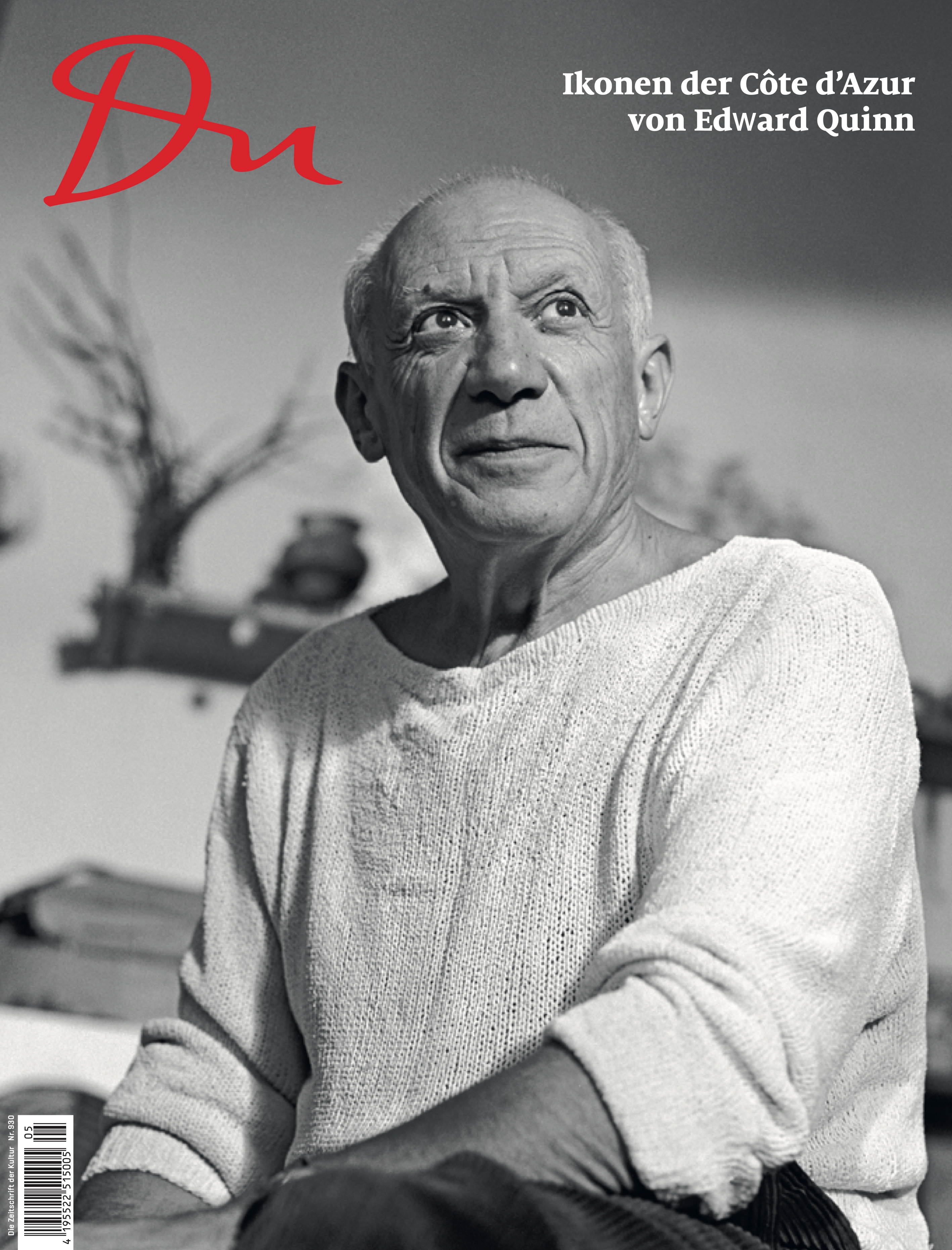

The Irishman Edward Quinn was the first photographer to take pictures of the celebrities on the Côte d'Azur on a large scale. From the Golden Fifties onwards, he traveled between Monte Carlo, Nice, Cannes and Saint-Tropez to get actors, artists, entrepreneurs and the nobility in front of his Leica. In those days, celebrities still moved around without bodyguards and press agents: entrepreneurs like Aristotle Onassis, actors like Brigitte Bardot, Alain Delon, Sophia Loren, Marlon Brando, Greta Garbo, Cary Grant and Marlene Dietrich, writers like Somerset Maugham, and artists like Pablo Picasso, Alexander Calder and Salvador Dalí.Quinn photographed them all. He even became friends with some of them. His friendship with Picasso began in 1951 and lasted until the artist's death in 1973. Picasso was already famous at the time. He liked Quinn and even allowed him to photograph him at work in Vallauris. Quinn visited him regularly for twenty years.

In this issue, you show a selection of Quinn's encounters. He recorded these himself. It often took him a lot of time and patience to gain the trust of the celebrities. He met Onassis for the first time at his estate in Cap d'Antibes. He didn't want to be photographed, but showed Quinn his photo album because he was proud of his ships and tankers. Onassis was rather small in stature, but he radiated a masculinity that attracted women, including the opera diva Maria Callas. Many described him as the most charming man of his time. Quinn was invited to the lavish, unforgettable parties on his luxury yacht Christina – and was also allowed to take pictures there. This is how countless contemporary documents came about.Quinn knew where to find the stars; large luxury hotels were particularly popular: the Hôtel de Paris in Monte Carlo, the Hôtel Negresco in Nice, the Hôtel du Cap d'Antibes and the Carlton in Cannes. Quinn was able to work freely for a long time. That changed drastically after the wedding of Prince Rainier and Grace Kelly in 1956, which attracted the interest of the world's press. From then on, a permit was needed for all official occasions. But Quinn was always among them: the rich and the beautiful – on the biggest and most beautiful stage in the world.

1 As a photographer on the Côte d'Azur

I was born in Dublin in 1920 and, like many other young Irish people, I realised that one day I would leave the country. During the Second World War, I earned a living as a musician in a jazz band in Belfast. After narrowly surviving a German air raid in a church, I joined the British Royal Air Force and served as a radio navigator in Lancaster bombers. With peace came a new vocation: I navigated charter aircraft on routes between Europe and Africa and in 1948 took part in the legendary Berlin Airlift during the Soviet blockade. In those days, my career path seemed to be mapped out. But when I met the Swiss woman Gret Sulser at the end of the 1940s and visited her in Monte Carlo, everything changed. With its timeless elegance, the Côte d'Azur had a special appeal for me - I was particularly captivated by the nostalgic grandeur of Monte Carlo with its dreamy harbour. At first I worked as a musician and performed under the name Eddy Quinero, Le célèbre Guitariste Electrique, in various bars and at dances. A friend lent me a Kodak bellows camera, and I went around snapping away, capturing images for memory, unconsciously already in the style of a reporter.

The local newspapers ran stories about the celebrities and stars who liked to come to the French Riviera, which was still untouched by big tourism. I realised that it could be worth my while to earn a living as a photographer with pictures of these celebrities and learned everything I could about photography from books and photo magazines. A Kodak Retina camera and an old enlarger became my equipment, followed later by a Rolleiflex and then a Leica, the standard cameras for press photographers at the time. My small flat in the historic centre of Monaco was not far from the Prince's Palace. In the beginning, I developed and enlarged my pictures in the kitchen under difficult conditions. Every time my landlady wanted to prepare dinner, I had to move all my equipment out of the way. A local journalist introduced me to the basics of press photography. He explained to me, for example, how I could find out the whereabouts of those who were worth reporting on and how best to approach them. In addition to the local newspapers, Nice Matin and Espoir, I also read the English dailies to find out which celebrities were coming to the south. But I soon realised that this information was not enough. Some stars preferred to stay unrecognised in a hotel or private villa. So I gradually built up a network of obliging bartenders, secretaries, doormen and reception staff at the most luxurious hotels along the coast. They gave me tips and they knew that I wouldn't reveal their secrets.

Photographing film actors offers one advantage: they are usually skilled at posing in front of the camera. But getting a picture that shows them as they really are backstage or away from the film set is more difficult. Many of the stars I photographed in the 1950s were at the height of their careers. When they came to the Côte d'Azur, they were looking to relax - sometimes they brought their families with them. The Hollywood stars in particular seemed to enjoy freeing themselves from the shackles of the studios and their agents. Nevertheless, it was by no means easy to interview or photograph them. It often took a lot of time and patience to gain their trust, and only rarely was I able to take pictures where I could freely arrange the scenery. I also worked without artificial light for portraits, at best with flash, but if possible I used the natural light available. This made the pictures more authentic and exclusive.

There were a number of places where you could be sure of meeting a star. Large luxury hotels were particularly popular - the Hôtel de Paris in Monte Carlo, the Hôtel Negresco in Nice, the Hôtel du Cap d'Antibes and the Carlton Hotel in Cannes. The glittering gala evenings at the Sporting d'Eté in Monte Carlo during the summer and at the International Sporting Club in winter attracted the rich and famous, and most of them attended. Hollywood stars were often invited to perform or add glamour to the event. For years, I reserved Friday evenings for gala events in Monte Carlo. Photographers could work there without restrictions as long as they didn't disturb the guests.

This changed dramatically after the wedding of Prince Rainier and Grace Kelly in 1956, which was reported everywhere. From then on, international newspapers and magazines were interested in everything that happened in the Principality. Permission was now required for all official occasions and strict instructions applied. Press agents took over and it became extremely difficult to work as an independent reporter.

In the fifties, film production flourished in the Victorine studios in Nice, the French Hollywood. Monsieur Clair, the director of the studios, would let me know when a scene with a famous actor or actress was being filmed. This is how my photos of the young Brigitte Bardot with her director and husband Roger Vadim, of Hitchcock and Grace Kelly during the filming of To Catch a Thief (1955); Frank Sinatra in Kings Go Forth (1958); Peter Ustinov in Lola Montès (1955). or David Niven, Jean Seberg and Deborah Kerr in Bonjour Tristesse (1958).

The Cannes Film Festival offered the opportunity to rub shoulders with a large number of stars from all over the world, but it was difficult for a reporter to have an exclusive or a first story when working alongside a mob of fighting and shouting rivals: the paparazzi. During the fifties, this mob of photographers, mostly Italians, invaded Cannes at every film festival. They behaved like a posse, surrounding the actresses and starlets and barking out their orders so that even the most famous top stars obediently obeyed. As they teamed up to stop other photographers from taking a picture, it was even harder to compete with them. While one of them cut off an actress to photograph her, the others blocked access as if to keep all the other photographers from their prey. Fortunately, I knew their strategies and usually managed to outsmart them. By using my various sources - the press agents, receptionists, friends - I had to try to anticipate where the stars would go. If I got a story first, even the paparazzi, with whom I was actually on good terms, were always ready to take credit.

Towards the end of the sixties, the character of the festival gradually changed. It became a combination of film screenings and a marketplace for distributors. The days when stars were really still stars were over. A new system emerged in which press agents strictly regulated contact between their protégés and the press. It became almost impossible to work as an independent journalist.

Another place on the coast where you could find at least one of the stars was Saint Tropez. The worldwide fame of this fishing town in the south of the Côte d'Azur dates back to the 1950s and is partly due to the new vehicle of freedom, the car. Of course, Brigitte Bardot also played a role in this. Until then, only a few artists and aristocrats had heard of this place and it was only visited by a small elite. Back then it was very difficult to get there - for a long time there had only been a rare bus service, or an old boat came over from St Raphael - but after mass tourism reached Saint Tropez in the 1950s, it was flooded with people, especially in summer, and lost its former charm.

I loved meeting celebrities and stars, but above all I enjoyed the company of artists and captured them in photographs - including Picasso, Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí and Francis Bacon.

It was an exciting, unique time on the Riviera in the fifties and sixties, characterised by optimism about progress. As Shakespeare wrote: "All the world's a stage and all the men and women merely players. They have their exits and their entrances." (All the world's a stage and all the men and women merely players, they have their exits and their entrances). The Côte d'Azur was one of the largest and most beautiful stages in the world at the time. Its performers were often magnificent and glamorous. Even though the curtain has fallen, the memories remain.

Edward Quinn, 1995

Bio

The Irishman Edward Quinn (1920 - 1997) lived and worked on the Côte d'Azur, where stars, managers, aristocracy and artists met in the Golden Fifiies in Nice, Cannes and Monte Carlo. His photos of celebrities such as Brigitte Bardot, Sophia Loren, Marlon Brando, Somerset Maugham, Aristotle Onassis and the Sinti and Roma in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer date from this period. His friendship with Picasso began in 1951 and lasted until the artist's death in 1973. During these twenty years, he produced an extensive photographic oeuvre about and with Picasso, which found expression in numerous exhibitions, books and films. In the early 1960s, Quinn travelled to Ireland several times with his camera. One result was James Joyce's Dublin, a book in which photos from Dublin are juxtaposed with quotations from Joyce's works.Inspired by his relationship with Picasso, Quinn increasingly focussed on working with visual artists from the 1960s onwards, including Max Ernst, Alexander Calder, Francis Bacon, Salvador Dali and David Hockney. Quinn has published several books on Picasso, Graham Sutherland, Max Ernst and Baselitz, among others.In the early 1990s, he moved to Altendorf on Lake Zurich and lived here with his Swiss wife Gret until his death in 1997. Today Wolfgang Frei, the photographer's nephew, and his wife Ursula look after the extensive Edward Quinn Archive, organise books and exhibitions, sell photos to collectors and license images for the media. (See edwardquinn.com)

2 Stars

Audrey Hepburn

On the set of the film "Monte Carlo Baby" at the Hotel de Paris in Monte Carlo, my attention was caught by an unknown actress who was playing a supporting role. I found out that her name was Audrey Hepburn. She had started her career as a dancer and had appeared in a few small roles in films. I was immediately intrigued and asked her to do a photo session. She agreed and we travelled to the picturesque surroundings of Monaco the next day. Not only was she an excellent model, but she also proved to be a friendly help by pushing my old Belgian Mathis car, which had run out of battery.

When I presented Audrey with the contact sheets the following day, she was very excited about the variety of poses and expressed the wish to be allowed to present these shots to her agent in Hollywood - a request that I naturally honoured. Her agent showed the pictures to the decision makers at Paramount Pictures and soon after she was invited to travel to America for screen tests. Eventually she got the lead role in the film "Roman Holiday."

Brigitte Bardot

Until the 1950s, the popular type of femininity was embodied by stars who had style and elegance, such as Ingrid Bergman, Greta Garbo or Michèle Morgan. But then the public's taste changed: a new wave of film stars, the denuded beauties, arrived. These seductive beauties were praised as sex symbols and the public, especially in America, admired the glamorous women with a pronounced bust and slim figure. This was the time when Brigitte Bardot made her debut. She was not yet 18 and practically unknown when I photographed her for the first time. She had come to the Riviera to shoot one of her first films: Manina, la fille sans voiles. She was an excellent model; as a ballet dancer, her movements were very supple, she walked and posed gracefully and it was clear why she was called Sex Kitten.

Sophia Loren

When I met Sophia in 1955, she was not yet a star, but a very attractive young woman with breasts that attracted attention wherever she went. Sophia was at a stage in her career at the time where a camera meant publicity and she was keen to get as much of it as possible. I had offered Paris Match to do a story on Sophia. Encouraged and always accompanied by her mother, she allowed herself to be photographed in all kinds of poses. She was prepared to lie on the bed in a magnificent white evening dress by Emilio Schuberth so that I could take an extraordinary photo.

A few years later, I photographed Sophia again in Cannes. At that time, she was already a celebrated star, admired not only for her looks but also for her acting. She had won an Oscar for best actress in Two Women. Sophia was now married to Carlo Ponti and they lived in the Hotel Carlton. A crowd of photographers swarmed around her and prevented anyone from taking an exclusive photo. At a press conference in their hotel room, I locked myself in the bathroom and only came out when everything was quiet because I didn't want to take the same photo as everyone else. After a moment of surprise and hesitation, Sophia accepted that I could take the pictures.

Marlon Brando

One day we heard that Marlon Brando was hiding out with a young woman in the small coastal town of Bandol. It was low season and it was not difficult for me to learn from the landlord of a small bistro that he had seen a stranger staying with a local fisherman in the Rue de la République. Two young girls gave me even more information: They knew that the handsome stranger was American and that he was the fiancé of Josanne Mariani, the daughter of a fisherman.

I was waiting discreetly in the car nearby, getting my Leica ready, when suddenly a Vespa scooter came round the corner in a cloud of dust. It was Brando with a girl clinging tightly to him. They stopped and quickly went into a house. I decided to wait, as I really wanted to take a few more photos of this extraordinary story. Brando was, after all, a great Hollywood actor, the star of Streetcar Named Desire and The Wild One, the heartthrob of the fifties. So it seemed incredible that he was living in a fisherman's house and courting an attractive but unassuming teenager. Josanne had met Brando at a party and they had fallen in love. Brando even told his friends that he was going to marry Josanne.

That afternoon, I was sitting in a café when Brando was walking along the seafront with Josanne. Brando saw me and as he didn't move away, I went up to him and he allowed me to take some pictures.

I just had time to send off my exclusive photos before Josanne's mum announced her daughter's engagement to Brando. Then a crowd of photographers and journalists flocked to Bandol, but Brando had already left for Rome. There he officially confirmed the engagement, but like many of Brando's romances, this love affair ended and Brando did not marry Josanne.

Grace Kelly and Prince Rainier

I met Grace Kelly when she came to the Côte d'Azur in 1954 to take part in the Hitchcock film To Catch a Thief. A year later, she returned to Cannes for the film festival. The editors of Paris Match magazine had the idea that a meeting between the bachelor Prince Rainier of Monaco and the Hollywood film star would make a good picture story. As I already knew Grace and had done an exclusive reportage on Rainier, I was chosen as the photographer to accompany Grace. On the way from Cannes to Monaco, I followed Grace's large limousine too closely to avoid being left behind and hit the car on a sharp bend. Fortunately, the only damage was to my car. At the palace, we learnt that the Prince was late. I suggested to his aide that Grace could have a look round the palace. I accompanied her and took a series of photos of this beautiful woman just before she met her future husband for the first time.

Finally, the Prince appeared and Grace Kelly, who had rehearsed her royal curtsy several times, barely bent her knee as she faced Prince Rainier. With a reassuring smile and a simple "Hello, pleased to meet you", the Prince seemed to put her at ease. I suggested we take a few photos in the palace gardens. That broke the ice. Prince Rainier was relieved and immediately agreed. Of course, my main reason for asking them outside was the typical photographer's reaction. The light was better outside and the garden would make a good backdrop. Rainier led Grace to a spot where he could show her the view of his principality. They were both relaxed now and they walked through his exotic gardens and to his tiger cage.

The pictures of Grace Kelly and Prince Rainier appeared in Paris Match, but the story was quickly forgotten, except probably by Rainier and Grace. According to his friends, the prince was fascinated by the cool, somewhat enigmatic star from Hollywood. The end of the story is well known. After the wedding of Prince Rainier and Grace Kelly, it became increasingly difficult to get exclusive pictures, as Grace had brought her own photographer from the USA. A development that set a precedent: the celebrities and especially their agents tried to gain more and more control over their photos.

3 Artist photos without artificiality

Wolfgang Frei, nephew of the photographer

We called him Ted, like his wife Gret. It was always a special event when the two of them came to Switzerland and brought a piece of internationality with them. Ted, my Irish uncle, who always carried a Leica and usually a Rolleiflex with him, the baggy pockets of his trench coat filled with yellow Kodak boxes and exposed film in canisters, fascinated me as a child with his English language, his pomaded black hair and his red moustache. But above all with his stories of stars I recognised from magazine covers and whom he had in front of his camera: Romy Schneider, Brigitte Bardot or Cary Grant, for example.

I often visited the Quinns on the Côte d'Azur and had the opportunity to assist him with projects, such as the book James Joyce's Dublin, in which he combined pictures of his home town of Dublin with excerpts from Joyce's texts. The archive in the small house high above Nice also served as a guest room. The bed stood next to a huge shelf with yellow Kodak boxes, labelled with all the famous names, from Picasso to Sophia Loren. This is where the prints were kept - back then intended for use in reproductions in newspapers and magazines, today they are valuable vintage prints.

The contacts, the 1:1 prints of the negatives, were also archived here. These show how the photographer worked: The order in which he took the photos, which image he selected at the time and which section he chose. These contact prints are valuable historical documents because they shed light on how the technology of the time led to a different photographic working method than today. Until the 1950s, for example, there were hardly any camera motors for taking continuous pictures. The typical fast, conspicuous click-clack that you always heard from professional photographers from the 70s onwards was not yet known in the 50s and 60s. Only the motors made it possible to take a large number of pictures in quick succession, from which the photographer later selected the best one. An entire film was often used for a single picture situation. In contrast, the classic contacts, which were taken without a motor, show that the selection of the "right" image was made - or had to be made - much earlier, when the picture was taken. Every single image had a value. Quinn did not use the motor later on either. Not only because of the disturbing staccato noise, but also because what mattered to him was the consciously photographed, decisive image, in the spirit of Anselm Adams: "The machine-gun approach to photography, that is, the hope that one good image will be found among many, has fatal consequences for serious photography."

With the digital cameras, the clack-clack also disappeared, the images could now be checked immediately after shooting and the costs of the film and the laboratory were eliminated. Today, it is hard to imagine that in Quinn's time it was only possible to determine whether the focus and exposure were correct and whether there was anything on the film at all after the film had been developed in the darkroom. The development from classic to digital photography gradually erased the significance of the unrepeatable decisive moment (Henri Cartier-Bresson), the decisive moment for a photograph.

Nothing was specially arranged by Quinn for taking pictures of artists. His aim was to show the conditions under which the artist created his works. He did not use a tripod and refrained from artificially illuminating rooms and positioning the artist where it was most favourable for the picture. Quinn rejected other photographers' pictures of artists taken in this way, even if the technical result was sometimes better. In his opinion, this was not a type of photography that showed the personality of the artist. He felt that even though they were excellent photographs, they remained stereotypical because they reflected the personality of the photographer rather than the subject. His aim was the unposed, credible shot, the authentic and documentary.

Quinn was not one of the paparazzi, the pushy celebrity photographers of the scandalous press. He was too much of an Irish gentleman for that: reserved, almost shy, although extremely persistent when he wanted to achieve a goal. He saw himself as a partner to the celebrities he photographed; photographer and model were supposed to co-operate and thus achieve the most positive result possible for both sides.

The most important collection in Quinn's archive are his photos of Picasso. There is no photographer who accompanied him over such a long period of time. After the first photos in 1951, he soon became a friend of Picasso, as his beautiful dedication dated 30 July 1954 on the linocut Toros en Vallauris shows: "Para el amigo Quinn - el buon fotografo" (For friend Quinn - the good photographer). Quinn was aware of the problem of being a friend of Picasso and at the same time a professional photographer, who necessarily had a journalistic interest in his subject first. His choice in this dilemma between professional distance and friendly closeness was clear; his friendship with Picasso was more important to him. Nevertheless, if the context of a sequence of images demanded it, he published photographs that Picasso may not have liked at all, but which he nevertheless tolerated because he respected the photographer's work. Picasso never asked to see his photographs in order to censor them before publication. Quinn's photographs show how Picasso was inspired by the everyday but also extraordinary things and people around him. This look at his personality, at the person behind the pictures, also reveals clichés about reality and contrasts: leisure alongside work, the everyday versus art, the womaniser and the family man, the extraverted clown and joker, but also the very thoughtful master.

4 Artists

Edward Quinn 1996

When I started working as a reporter on the Côte d'Azur in the early 1950s, I was not yet familiar with the names of contemporary artists. Of course, I had heard of Picasso and soon found out that he lived somewhere nearby. His name exerted a magical attraction on editors of newspapers and magazines, and I was made aware very early on that a report on Picasso would be very welcome.

My first encounter with Picasso on 21 July 1951 was no coincidence. I learned from a local newspaper that he was expected to be the guest of honour at the opening of a ceramics exhibition in Vallauris. Despite my inexperience as a photojournalist, I recognised my opportunity. During the exhibition, Picasso was surrounded by photographers and local dignitaries, so getting a good shot was impossible and I waited until the press had left. This was all the better as shortly before Picasso said goodbye, the housekeeper turned up with his children Claude and Paloma. I took my chance and photographed Picasso with Paloma in his arms and little Claude next to him. That one picture was the beginning of my friendship with Picasso. He liked the photo, and shortly afterwards he allowed me to photograph him at work in his ceramics workshop in Vallauris. It was a formative experience for me to watch Picasso at work. I had never witnessed the creation of a work of art before. It was with great relief that I heard Picasso say to Madame Ramié, the owner of the Madoura ceramics workshop, at the end of the working day: "Lui, il ne me dérange pas" ("He doesn't bother me"). This meant that I was allowed to visit him again, and in fact I was able to visit and photograph him regularly over the next 20 years.

In 1964, I was commissioned by the New York Times to photograph Max Ernst, and I was able to make a reportage about him in his house in Seillans, a small town in Provence. Ten years later, after studying his work intensively, I had the idea of making a book about him that would combine his pictures and his autobiographical "Notes for a Biography" in the style of a collage. I hadn't seen him again since the meeting I mentioned. I hoped to meet him again in Seillans, where I had photographed him for the first time. Max Ernst received me, but was very irritated because I had disturbed him while he was working. I explained my book project to him, but he flatly refused any co-operation. It was months before I got another appointment, so I travelled to Seillans with the first drafts. Max Ernst looked at them carefully and finally said: "Mr Quinn, I like your work very much". Afterwards, he invited me to dinner with his wife Dorothea Tanning, to which he brought an excellent wine from the cellar.

From then on, I paid frequent visits to Max Ernst. The book was published in 1976, the year Max Ernst died. He made one of his last works, a lithograph, especially for this book. I was very touched when I learnt that he, now seriously ill, had signed the sheets on his sickbed.

Jean Cocteau was one of the most prominent figures on the art scene on the Côte d'Azur. He was known as a novelist, lyricist, playwright, film-maker and painter. Cocteau was only too happy to receive journalists and always made his guests feel at home. He always had something to tell or something new to show, and the journalists left him with new information and good pictures. As a filmmaker, Cocteau knew exactly how to put himself in the limelight.

He lived at Cap Ferrat at the invitation of Francine Weisweiller, a well-known lady from Parisian café society. She owned the enchanting Villa Santo Sospir. To return the favour of Madame Weisweiller's generous hospitality, Cocteau decorated the white walls of the villa with paintings, drawing inspiration from mythological stories and heroes. In 1956, he worked on the immense task of renovating the old, almost abandoned Saint Pierre fisherman's chapel in Villefranche. When choosing his motifs, he was inspired by the Bible and depicted three episodes from the life of Jesus. He used local fishermen as models for the murals.

In 1953, I photographed Marc Chagall and his second wife Valentine Brodsky in their house in Saint Paul de Vence. As Chagall tended to concentrate on his work, he was reluctant to be disturbed. He preferred to withdraw into his fantasy world of peasants, animals and flowers. His garden was full of flowers, and he once declared that painting must always try to compete with the beauty of flowers, but must always settle for second place.

In 1964, the Fondation Maeght was founded in Saint Paul de Vence by art dealer and collector Aimé Maeght. He wanted to create a meeting place for art lovers. Through the collaboration of Miró, Chagall, Giacometti, Tal Coat, Ubac and others, the "Fondation Maeght" became a collective work of art. Joan Miró created sculptures such as L'Oiseau lunaire and the large Oeuf cosmique as the centrepiece of a small pond, where I photographed him together with Aimée Maeght.

On the day of the opening of the Fondation Maeght, Alberto Giacometti visited the room containing his sculptures alone. I happened to be there too and had the opportunity to observe the artist as he looked at his work, while his figures in turn seemed to be watching him.

I met Alexander Calder when he visited Aimé Maeght in Saint Paul. When I photographed him, he proudly showed me his little mobiles. He was in a very good mood and was happy every time a gust of wind blew the mobile around while he tried to keep the centre of rotation steady.

When I visited Salvador Dalí in Portlligat on the Costa Brava

in 1957, he showed me his.

latest discovery. For this special occasion, he wore a special costume consisting of a richly decorated jacket with a matching cap. He introduced me to a sea urchin called Sputnik and demonstrated how it painted a picture. First, he inserted an extremely light swan feather into the mouth of the urchin, which functioned like a hand with its five teeth and held the keel in place. He then placed the sea urchin and feather in front of a sheet of blackened paper, and with movements that Dalí described as controlled by the cosmos, the sea urchin drew decorative lines on the paper. Dalí insisted that some urchins were more talented than others. It was a remarkable day, and I was delighted with the images, which the English newspaper Sunday Graphic published in an article entitled A COSMIC SENSATION.

In the 1950s, Georges Simenon lived in his Golden Gate villa in Cannes. As I enjoyed doing reportages sur le vif, I asked him if I could accompany him on a typical day. I was surprised that he started work at 6 o'clock in the morning. He began his morning ritual by pacing back and forth on the terrace, hands clasped behind his back, nervously fiddling with a rosary of Turkish amber beads. Before going to work, Simenon also did a few simple gymnastic exercises on a board he had had specially made. While he made a pot of coffee, he told me that he writes about five books a year and that it takes him about 11 days. He couldn't stand the effort any longer than that. After the coffee, he wrote with one of his countless finely sharpened pencils until around 10 o'clock, read through the manuscript and typed it into. The machine. Then his working day was over and he went shopping at the market, followed by an aperitif in a small bar that looked like one of his Maigret novels.

When I first met Françoise Sagan, she had just driven from Paris to Cannes in her Jaguar. She was writing her second novel Un Certain Sourire in a room overlooking the sea at the Hotel Carlton. Françoise said that she could only work for two hours a day, that was all she had energy for. To write, she preferred to lie on the floor or balance her typewriter on her lap while sitting in an armchair. Un Certain Sourire also became a bestseller. The book is about a love affair between a young girl and a man twice her age. Sagan's fictional story came true when she later married her wealthy publisher Guy Schoeller, who was about 20 years older than her. However, the marriage did not last long.

Somerset Maugham owned the Villa Mauresque in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat. With the sale of more than 40 million books, he had become a very rich man. Maugham began his day by smoking a pipe in bed and reading the daily newspapers. Almost until the end of his life, he kept to a strict work routine. Every day he went to his writing room on the roof. He once said to me "I always thought life was too short to do something you could pay someone else to do. And now I've become rich and can afford the luxury of only doing what nobody else can do."

I photographed artists not only on the Côte d'Azur, but above all in their studios in England and Ireland: David Hockney, Sam Francis and Louis le Brocquy. I was particularly close to Francis Bacon, who, like me, was born in Dublin. I remember well one of my first meetings with him in 1978 in London at 7 Reece Mews. He took me into the tiny kitchen of his studio flat and we were joined by his cleaning lady - or 'cleaner-upper' as Francis would say when he used his cockney slang. She made us both a cup of strong English tea and we stood there chatting and sipping it. I couldn't help but wonder what she thought about the paintings that filled the rather untidy studio.

I found it hard to imagine how the elderly lady managed to climb the narrow staircase, which looked more like a ladder and led to the top floor. Just as I wondered how Francis managed the stairs after one of his legendary nights in London restaurants, where he drank more alcohol than two big men could normally handle. But Francis could stay very sober, at least after a bottle of champagne or a few glasses of whisky.

I remember that I had to undergo a kind of test before Francis accepted me. After our first real meeting, he invited me to his favourite restaurant in Soho. A four-course meal awaited us there, during which I drank at least four times as much alcohol as I was used to. Nevertheless, I managed to have a more or less intelligent conversation about art, especially about Picasso, whom Francis Bacon admired and respected enormously. I can no longer say exactly how that evening ended, but whatever happened, I must have behaved decently, because I had passed the entrance exam for Francis Bacon's circle of friends, his exclusive club.

Much later, I was able to get to know the creative side of the artist. Francis allowed me to photograph him in his studio: an impressive experience. From then on, I met him several times in London, and each time we supplemented the work sessions in his studio with conversations in the cosy atmosphere of a restaurant in Chelsea or Soho. Francis enjoyed just talking. Our photo sessions were limited to photographing him in his flat or at the Marlborough Gallery - and occasionally in his Paris studio. Francis didn't like talking about his art, and I didn't press him on the subject.

5 Aristoteles Onassis

The Onassis story began for me in 1953, the day I was asked by TIME magazine to take a photo of a Greek who had bought a substantial block of shares in the Monte Carlo casino. My research led me to one Aristotle Onassis, the owner of a whaler that was anchored off Nice at the time. At the harbour, I managed to photograph a man whose appearance matched the description; however, it turned out that it was not Onassis, but one of his Greek business partners. He informed me that Onassis resided in the villa Château de la Croë - situated on the Cap d'Antibes.

The stately villa was enthroned in the middle of an extensive park right on the coast and was known as the retreat of the Duke of Windsor and Wallis Simpson during their honeymoon - after he had renounced the English throne for her. A maître d'hôtel dressed all in white greeted me at the door; Onassis appeared shortly afterwards. With a smile, he listened to the reason for my visit and immediately replied: "I'm not a film star and don't want to see my likeness in the press." Nevertheless, he allowed me to take a look at his photo album and invited me to take any pictures of my choice - many of which showed a proud Onassis in front of his ships or tankers at their christening with a bottle of champagne. I replied that as a photographer I preferred to create my own images. Onassis just shrugged his shoulders and took his album back, and I left disappointed.

Coincidentally, on the same day I was invited for a drink with some other journalists in Spyros Skouras' room at the Hotel Negresco in Nice. Skouras was then head of the film company 20th Century Fox, and a French inventor, Professor Chretien, had just sold him his latest invention, the Cinemascope widescreen lens. In conversation with Skouras, I mentioned my meeting with his compatriot. At that moment, the phone rang and Skouras picked it up. With a smile on his face, he said into the phone: "Why don't you drop by?" A short time later, Onassis entered the room and was naturally surprised to see me. Skouras, in high spirits, said to Onassis: "You weren't very co-operative with our friend from the press. Come on, Ari, let's take a photo together." Onassis laughed and sat down somewhat reluctantly next to Skouras, who cleared away all the drinks (so as not to upset the American League of Teetotallers). This was my first press photo of Onassis - probably also the first to show him to the public.

I had the privilege of taking many exclusive pictures of him with his wife Tina and their children Alexander and Christina at the Château de la Croë and on the yacht. Tina Onassis, the daughter of the Greek shipping magnate Stavros Livanos, who was just as important as her husband Aristotle Onassis, had been educated in England and the United States and spoke fluent English, and I always got on very well with her.

Onassis had gone to spectacular lengths to impress her. He once raced past Tina in Oyster Bay, Long Island, in a speedboat, carrying a banner with the letters T.I.L.Y. (Tina I love you). Onassis also gave her a gold bracelet with a gold coin that read Saturday, 7 p.m. 17 April 1943, T.I.L.Y.. When she asked what the inscription meant, Onassis said: "That was the day I fell in love with you." Tina was only 14 years old at the time. Although Onassis was rather small in stature, he exuded an obvious masculinity that attracted women. Many of them described him as the most charming man of their time. In addition to his luxurious lifestyle, it was above all his charismatic charm that made him so popular. Women appreciated his attentiveness and the feeling of being unique.

This must also have been the case for the opera diva Maria Callas. A friendship developed between them during a trip on the Christina. Together with her husband and impresario Giovanni Meneghini, an Italian millionaire, they were invited on a three-week cruise through the Gulf of Corinth with Sir Winston and Lady Clementine Churchill and a few other guests. Shortly after leaving Monaco, they ran into bad weather. Most of the guests on board became seasick and had to stay in their cabins. The only exceptions were La Callas and Onassis, who were left alone on deck for many hours, especially at night. On her return, Maria confessed to her husband that she had fallen in love with Onassis. Friends said that La Callas was the right partner for Onassis, but although she left her husband, she never married Onassis.

First-class luxury awaited the passengers on board the Christina. The ship, originally a Canadian frigate, was converted into an exclusive luxury yacht by Howaldtswerke. Onassis insisted that all modern conveniences, including the latest air conditioning and electronic equipment, be installed. In addition, a cinema, a sick bay and an operating theatre with X-ray facilities were built.

Onassis himself resided in a magnificent three-room suite on the Christina. Above his Louis XV desk hung a painting by El Greco, flanked by two golden swords - gifts from Ibn Saud, the founder of Saudi Arabia. In the bathrooms, golden taps in the shape of dolphins adorned the washbasins. Each of the guest suites was named after a Greek island and individually designed by a different artist. The Chios stateroom was reserved exclusively for Churchill and featured a customised night reading lamp above the bed. All cabins were equipped with telephones for 24-hour room service and even allowed transatlantic calls.

The swimming pool on the aft deck of the Christina was a real showpiece. It was covered with a mosaic depicting a scene from Greek mythology: the Bull of Minos - a copy of the floor in the Palace of Minos in Knossos. At the touch of a button, the pool could be lowered to a depth of 2.5 metres and then filled with warm seawater. When required, it was transformed into a 15 square metre dance floor. Aristotle Onassis once surprised Winston Churchill by lowering the floor while Churchill was sitting there. In retrospect, Churchill was amused by the joke, although he initially feared taking an unwanted bath.

The Louis XV-style dining room was decorated with four murals by the French artist Marcel Vertés. In the games room there was a large fireplace made of lapis lazuli, Onassis' favourite stone, and in one corner stood a grand piano. Among the paintings in the library and playroom were portraits of Tina and the children Christina and Alexander. When Winston Churchill gave Onassis one of his paintings as a gift, it was given pride of place in the reception room.

A variety of aperitifs and liqueurs were on offer in the cosy bar. The bar stools were upholstered in white whale leather. When Onassis saw a female guest sitting on one of these stools, he liked to joke: "I hope you don't mind, but you happen to be sitting on the genitals of a giant whale."

Onassis frequently invited celebrities on board the Christina and to gala dinners in Monte Carlo. He favoured Hollywood stars such as Greta Garbo, Cary Grant, Marlene Dietrich, Frank Sinatra, Ava Gardner, Gary Cooper, John Wayne and Sammy Davis Jr. His guests were cosmopolitan, and his parties were also attended by aristocratic guests. Princess Marie-Gabrielle of Savoy, her sister Maria Pia with her husband Prince Alexander of Yugoslavia, the Maharanee of Baroda, the Rainiers, former King Peter of Yugoslavia and his wife Princess Aly Khan were among them. Of course, important personalities from the shipping and oil business were also present.

The publicity he received through his connections to famous personalities certainly helped him with his business projects. As soon as he made an interesting contact, he used his entire fortune, his luxurious boat and his famous friends to negotiate complex contracts with persuasive charm.

I often had the pleasure of being on board the Christina when Aristotle Onassis organised one of these lavish, unforgettable parties. As one of the few photographers allowed on board, I was free to take pictures. We had a gentlemen's agreement, so to speak. Onassis and Tina appreciated my work and respected me. They saw the photos in the magazines and never objected to any of them.

The evening on board always began with cocktails served at the edge of the swimming pool and in the games room. Onassis did not prefer fancy drinks, but his favourite Greek beverages: ouzo and mezés. He was a master at making every guest feel welcome. Even when the yacht was overcrowded, he found a moment for everyone. He moved between his guests, paying just as much attention to the pretty mistress of a businessman as to a rich industrialist with whom he was negotiating business deals. He was even diplomatic enough to speak to his arch-rival and brother-in-law Niarchos.

Aristotle Onassis' wife Tina played a central role at these brilliant receptions. However, she eventually had enough of her husband's addiction to publicity and the endless high life that had become an essential part of his life. The liaison with Maria Callas and several other affairs eventually led to Tina filing for divorce. She explained the breakdown of their marriage by saying: "I always liked simple things, but Ari began to favour extravagance. He was a wonderful person, but after he took over in Monte Carlo, his success in high society spoilt him and ruined our life together."

When Onassis met Winston Churchill, he knew that this was the most important meeting of his life. The two men met through Churchill's son Randolph, who was a friend of Onassis. Sir Winston accepted an invitation to lunch with Onassis in Monte Carlo and the two took an instant liking to each other. That day began a friendship that lasted until Churchill's death.

Onassis was so concerned about Churchill's well-being that once, when he was expected on the Christina, he lay down on the bed in Sir Winston's cabin. He then had the chief engineer run the engines at different speeds to find the cruising speed that caused the least vibration.

Churchill always brought his budgie Toby with him to the Riviera. One day, the parakeet decided to enjoy the Mediterranean air and flew away. Churchill was so depressed that Onassis organised a search operation, not only in Monte Carlo, but along the entire coast. The police and fire brigade were mobilised and Onassis nearly went mad and didn't even go to bed while he led the search operation. Fortunately, the budgerigar got tired and was found 20 kilometres away near Nice.

6 Pin-ups

When I started out as a photographer in the early 1950s, pictures of people-in-the-news were the most sought-after by the press. But there was also a big market for glamour photos and the editors knew exactly what kind of pictures they wanted. The American National Enquirer, for example, sent me copies of pictures they had used and wrote: "As you can see, we favour the bikini swimming costume and the type of figure that fills it out well." Articles appeared in trade journals explaining how to get the best pin-up pictures. They recommended choosing the girl who was best suited to the project from the agencies' model lists. They gave advice on what props to bring to make a more vibrant image, any bits and bobs to break up the visually boring sand or a guitar to add a special touch to the image. Certain natural elements on a harbour, an anchor or a fishing net for example, should be used as suggestive elements. The models should have lacquered, shiny hair or let it blow freely in the wind. A make-up kit should be kept ready in case the make-up needs to be improved. Pancake N25 from Max Factor is very suitable for black and white photos, while the 3N can be used for colour photos... All this well-intentioned advice didn't help me much, because most of my shoots were improvised. Back then, glamour or pin-up photos were part of a photographer's routine. Pretty women were still happy when their picture was published in a newspaper or magazine, but it wasn't possible to choose models from a list. There were no modelling agencies on the Côte d'Azur, so I had to find the attractive girls myself.

The most obvious place was, of course, the beach. Whenever I saw a girl who was likely to be photographed well, I simply approached her and asked politely if she would allow herself to be photographed. They usually agreed readily, but you didn't have long to look for a suitable background or ask them to change their hairstyle or costume. I had to make the best of the given situation. I also followed the beauty contests that often took place on the Riviera, where the "Reine de la Côte d'Azur", the "Reine de Nice" and other queens were chosen. If the girls were really pretty, I tried to photograph them again on another day. I always looked for women with a natural smile, not the ones with the "say cheese" smile.

I had the opportunity to meet an extraordinary girl, Greta from Denmark. She had come to Nice for a holiday. I noticed her on a walk along the Promenade des Anglais. With a series of photos of Greta, I managed to break into the magazine cover market. Illustrated, one of the big magazines in England, used a cover and a series of photos and even organised a readers' competition to choose the picture with the most popular pose.

I have photographed a large number of very attractive women; none of them were professional models. Many became film actresses, others married famous men - the American model Gregg Sherwood married the car manufacturer Horace Dodge; the beauty queen Myriam Bru married the German actor Horst Buchholz; the French fashion model Eliette Mouret became the wife of the conductor Herbert von Karajan. Glamour photography could be quite useful - you would often get a few pictures of a pretty girl spotted on the beach after trying in vain to find a news personality of interest to the press.

When I was looking for photo material for a film project about pin-ups, I was amazed to discover that most of the pictures I had taken at the beginning of the 1950s could still have been taken in the same way today, 40 years later. The swimming costumes or beach dresses, the hairstyle, the make-up - nothing seems to differ from today's fashion. Things were different 50 years earlier: of course the beaches have changed - secluded spots on the Côte d'Azur have become rare. If you think back to photos of young ladies taken at a fashionable summer resort at the beginning of the 19th century, the difference to the girls I photographed in the 1950s seems enormous. You can see pictures of practically fully clothed ladies carrying a pretty parasol and dipping their feet in the sea on the shore. No comparison with the pictures from the fifties.

7 Côte d'Azur: A chronicle of glamour and crises

The Côte d'Azur's reputation as a unique meeting place for the rich and famous began in the middle of the 19th century. At that time, the area known as the Riviera also included the Italian Riviera di Ponente and the Riviera di Levante. To distinguish the French Riviera from its Italian sisters, the writer Stéphen Liégeard later coined the poetic name "La Côte d'Azur" - the Blue Coast.

The French Riviera had no clearly defined boundaries. Kings and queens, aristocrats, the European aristocracy, the society of millionaires, the beautiful people of the time and, of course, writers, painters and musicians who were in vogue, all raved about this lush and exotic 100-kilometre stretch of Mediterranean coastline - from Menton on the Italian border to the beaches of Saint-Tropez and beyond to Bandol and Cassis. The glamorous Monte Carlo, the quiet city of Nice and the elegant old town of Cannes were particularly popular. Attracted by the mild climate with its eternally blue sky, the refreshing sea breeze and the beguiling scent of pine, eucalyptus and mimosa bushes as well as the lush variety of wild herbs, the Côte d'Azur cast a spell over the rich and beautiful. In the 1880s, this coastal strip developed into a winter holiday destination par excellence. The list of prominent guests reads like a Who's Who of the elite of the time, led by the honourable Queen Victoria of England, whose regular visits are immortalised to this day in the numerous hotels that bear her name. Thanks to its kinship with many European royal houses, the Côte d'Azur provided a stage for relaxed encounters with Her Majesty. The illustrious society that spent the winter on the Côte d'Azur belonged to European high society before the First World War: Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria, the fascinating Eugénie, former Empress of France and wife of Napoleon III, King Leopold II of Belgium and the Russian Grand Duke Sergei Romanov were among the select guests.

Monte Carlo was the centre of attraction for royalty. In the winter season of 1887 alone, the Queen of Portugal, the King of Sweden, the Emperor and Empress of Austria, the King of Belgium, the Russian Dowager Tsar and the King of Serbia honoured themselves there. Monte Carlo was already a unique place for gamblers back then, and quite a few lost a large part of their fortune here.

The discovery of the Côte d'Azur goes back to Lord Henry Brougham, a Scottish politician and lawyer. In November 1834, while travelling from the south to Italy, a cholera epidemic forced him to stop in Cannes. In this picturesque fishing village overlooking the Iles de Lerins, he fell in love with the modest Provençal houses, the small harbour, the red rocks of the Esterel and the tempting bouillabaisse. He stayed at the only inn, the Auberge Pinchinat, and barely a week after his arrival he bought a large property there. In a letter to a friend in London, he wrote: "In this enchanted atmosphere, which appeals to dreamers like me, it is a pleasure to forget for a few moments the ugliness and misery of life." He returned to Cannes the following year, and many of his friends came with him. The legend of the Golden Riviera was born and the European aristocracy began to discover this enchanting region for themselves. A winter visit to the Côte d'Azur soon became an integral part of the social calendar. In 1839, Brougham had the imposing Villa Eleonore-Louise built, which still exists today. He thus laid the foundations for a building boom that produced exclusive villas with magnificent gardens in the years that followed - some of the most famous villas on the Riviera date from this period.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the rigid social barriers began to loosen. A new, more frivolous atmosphere spread, no doubt fuelled by the notorious bon vivant, the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII), and his sometimes dubious entourage. Hotels were built to accommodate this illustrious society and casinos to entertain them. Another Englishman, Henry Ruhl, who started out as a bellboy at the Hotel Scribe in Paris, made a fortune building and running hotels. He planned and built houses with luxurious flats for kings and queens as well as the wealthy. His most famous creations were the Ruhl in Nice and the Carlton in Cannes. In each of these luxury hotels, an entire floor was reserved for royal guests.

During this time, the Riviera was a playground for the super-rich and those who enjoyed life where the money was. Exclusive artists were hired to entertain these privileged circles. The Russian impresario Djaghilev staged brilliantly choreographed ballets in the Monte Carlo Opera House, with Anna Pavlova and the legendary Nijinsky as outstanding performers. Famous musicians such as Berlioz and Paganini appeared, not only at concerts, but also as central figures in social life and as star guests at the extravagant parties in the magnificent villas by the sea.

These opulent parties were often financed by wealthy industrialists and businessmen. The American millionaires J.P. Morgan and Cornelius Vanderbilt owned luxury yachts that cruised along the Riviera, often with royal guests on board. At the end of the 19th century and into the late 1920s, until the stock market crash of 1929, the word "Riviera" was synonymous with wealth, elegance, high living, romance and intrigue.

The Côte d'Azur was an inexhaustible source of inspiration for novelists, but reality often surpassed even the boldest literary fantasies. Sentimental love affairs and spectacular jewellery robberies dominated the stories, while tragic suicide tales of hapless businessmen and aristocrats gambling away their fortunes were widespread. One particularly gloomy legend tells of a casino employee who is said to have put a loaded revolver in the pocket of a desperate gambler as he left the house.

As the Riviera grew in popularity, it increasingly attracted wealthy visitors, who were not always in the millionaire class. The French railway company recognised this and decided to make the most important places on the Côte d'Azur more accessible by opening up a railway line. In 1868, the PLM railway (Paris - Lyon - Méditerranée) was completed, running from Marseille to Monte Carlo and as close as possible to the sea so that travellers could enjoy the breathtaking panorama to the full. The elegant waiting rooms of the railway stations in St Raphael, Cannes, Nice, Monaco, Monte Carlo and Menton were richly decorated with ceramic tiles, tapestries and landscape paintings, opening up the coast to a new clientele. To cater for the growing seasonal crowds, numerous new hotels were built - not only in the glamorous seaside resorts, but also in smaller towns such as Menton, Beaulieu, Antibes and Juan-les-Pins, which were less well-known at the time.

The Riviera's prosperity and success peaked when the stock market crash on Wall Street destroyed the financial foundations of many foreign regulars on the Côte d'Azur. Some were forced to close their extravagant properties and lay off their staff. This exodus led to properties and large residences being offered for sale at ridiculously low prices. As a result, the Côte d'Azur had to rely largely on the French population to survive economically. But at the end of the 1930s, as the financial world recovered, prosperity returned to the Riviera. New buildings such as the Palais du Sporting Club in Monte Carlo were erected to delight the nouveaux riches with food, dance and entertainment. Until the outbreak of the Second World War, the Riviera experienced a revival of joie de vivre, elegance and eccentricity that made the headlines of the time. The Côte d'Azur was the scene of concours d'élégance, carnivals, gala dinners, balls, ballets, operas, the Monte Carlo Rally, the Grand Prix de Monaco, concours hippique and clay pigeon shooting.

With the start of the Second World War, the magnificent houses were once again shuttered and valuable objects, jewellery and paintings were carefully hidden away. Life on the coast changed: the locals looked after the region, but the once magnificent villas fell into disrepair and the large gardens became overgrown. The Riviera acquired the morbid splendour of past greatness. In 1941, a demilitarised, so-called free zone was established in the south of France that was not occupied by the Germans, which fortunately brought peace to the region for the most part. There were only isolated instances of war activities, which were limited to the shelling of strategic points on the coast. Buildings along the coast were damaged, particularly during the invasion in 1944 and the bombardment when the allied troops landed. St Tropez was one of the hardest hit places and many houses along the famous harbour suffered severe damage.

After the war, people gradually returned to the Riviera, but for many, living conditions and financial circumstances had changed fundamentally. The world seemed irrevocably different, and this impression led to many villas and second homes in the south being neglected. Between 1945 and 1949, houses and land were therefore once again available for purchase at comparatively low prices, resulting in a significant redistribution of private property. Nevertheless, the unique lifestyle that was still possible on the Riviera began to attract visitors again. The most important hotels and casinos were lavishly renovated and reopened in the luxurious splendour of the pre-war era. In the first years after the war, American tourists flocked to the Côte d'Azur - the dollar was the hardest currency in the world and extremely popular in the tourism business. Everything was done to cater for both the enthusiastic and the less discerning globetrotters. Former kings and queens, aristocrats, playboys, stars and starlets, exiled politicians and tycoons also found their way back to the French Riviera. A new generation of celebrities, the jet-setters, established themselves, while artists remembered the peace and beauty of the Côte d'Azur. Many famous painters, writers and poets came to settle and work here.

Most people sought refuge on the Riviera from the hectic atmosphere created by the reconstruction of the big cities after the war. I experienced this glamorous era of the Côte d'Azur, the golden 50s and 60s, at close quarters and captured it with my camera.

Edward Quinn, Nice 1980