Pablo Picasso

My first opportunity to photograph Picasso came in 1951 at the ceramics exhibition in Vallauris, where Picasso had been living and working since 1947. Naturally I was not the only one who wanted to see Picasso on that day. Also waiting in the crowd of spectators and potters was Prince Ali Khan, another name that produced headlines. Picasso – who was not always in a pleasant mood, as I later learned – came to the exhibition smiling amicably, accompanied by a friend, the poet Jacques Prévert. Like a bishop visiting one of his parishes, he strode through the waiting crowd, smiling with his head slightly bowed. When he saw potters that he knew, he occasionally stopped and spoke to them.

Françoise Gilot, his constant companion at that time, followed him inconspicuously and was engaged in conversation with Prévert. The reception committee was awaiting him at the entrance to the exhibition. Nothing phased him. In the exhibition at last, Picasso, the passionate craftsman, only showed interest in the objects. He carefully examined the ceramics on display and talked with the potters, discussing firing methods with them.

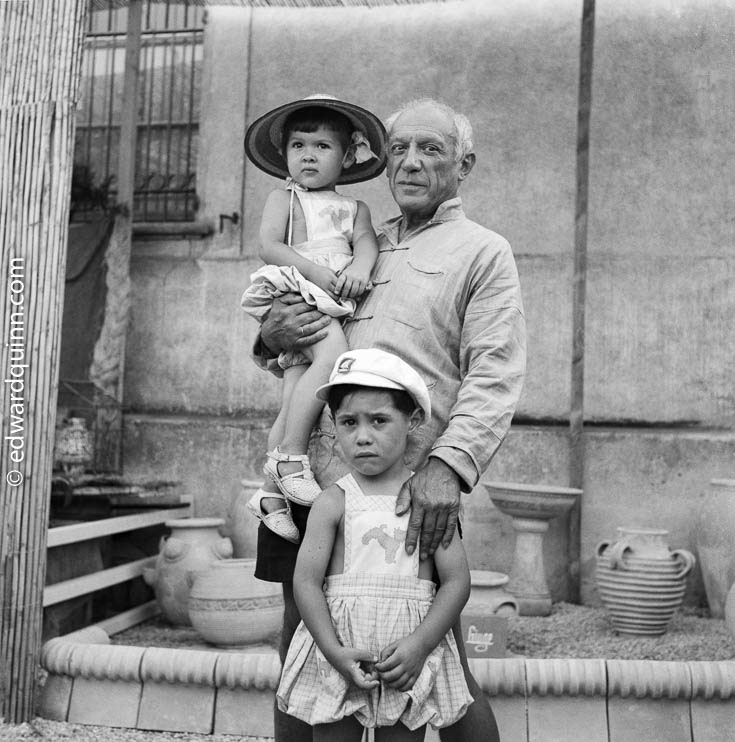

But Picasso’s own work was also on display – plates with bullfight scenes and mythological subjects, the themes with which he had begun his ceramic endeavours under the direction of Suzanne and Georges Ramié. Together with the mob of photographers, I followed Picasso through the exhibition. We pushed and shoved to get a good picture, and I had difficulty even trying to photograph. I didn’t want to use a flash, and since the light in the exhibition hall was poor, I had to try to stand still in the crush for a longer exposure. When Picasso then began to converse with Ali Khan, it was clear to everyone that the two quite different celebrities wanted to pose for the photographers’ flashes for a moment so they would finally be left in peace. After pictures had been taken, all the photographers rushed to their press agents. I was not under contract, so I stayed. It paid off, for just as Picasso was about to leave, his housekeeper came with his two small children, Claude and Paloma. Spontaneously, I asked Picasso if he would pose for me with his children. He was in a great mood and agreed. Afterwards, we spoke with one another for a few minutes, at which point I asked his permission to photograph him in his house. He politely refused: “We’ll see.”

The first few pictures I had taken of Picasso and his children pleased him so much that after a few refusals, he did finally agree to allow me to photograph him in his pottery studio in Vallauris.

My first appointment with Pablo Picasso in his pottery workshop was nerve-racking and difficult. I was afraid that my cautious and timid movements between the rows of stacked-up ceramics might disturb him. To me the click of my camera’s shutter seemed to resound like thunder in the atelier. Picasso, though, who was sitting beneath the statue of St. Claude, the patron saint of potters, worked with concentration, deeply engrossed and not even taking note of me. I was very excited in this atmosphere. Picasso’s all-commanding presence, his reputation as an artist, and the fact that I was seeing him at work for the first time spurred me on to preserve those intense, quickly passing moments. I felt secure enough to experiment more than I usually did, choosing different angles, and making use of unusual lighting conditions. When the workday with Picasso came to an end, I felt very relieved and encouraged upon hearing him say to a friend, “Lui, il ne me dérange pas.” (He doesn’t disturb me.) Now I knew that I would be allowed to continue photographing Picasso unhindered in the future. And truthfully, from that day on, I remained one of the few photographers allowed to visit and photograph him at work and one of the very few he ever tolerated in his private domain. This gave me the unique opportunity to take Picasso’s portrait carefully over many years.