Quinn’s biography

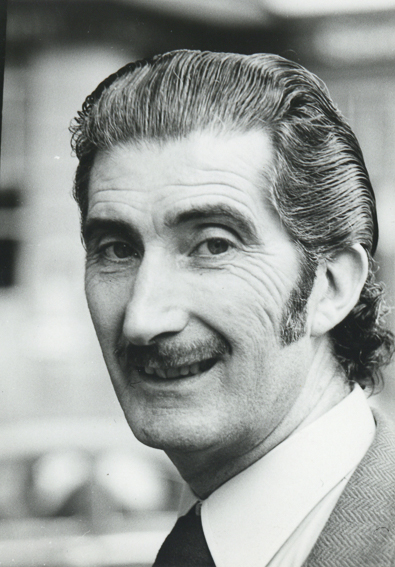

Edward Quinn, or “Ted” as his family called him, was born 1920 in Ireland. Starting in the 1950s, he lived and worked as a photographer on the Côte d’Azur, which was a playground for celebrities from the world of show biz, art and business during the “Golden Fifties”. The rich and famous came to the Riviera to relax. But the movie stars recognized the importance of their off-screen image, and Quinn was in the right place at the right time, managing to capture spontaneous and enchanting images that documented the charm, sophistication and chic of a legendary era.

In 1951, Edward Quinn met and photographed Pablo Picasso for the first time. Their friendship lasted until Picasso’s death in 1973. This encounter with Picasso had a lasting influence on Quinn, both personally and in regard to his subsequent work. Quinn is the author of several books and films about Picasso.

Starting in the 1960s, Quinn concentrated his professional activities on artists, photographing such figures as Max Ernst, Alexander Calder, Francis Bacon, Salvador Dalí, Graham Sutherland and David Hockney. In the late 1980s, a close relationship – similar to his friendship with Picasso – developed between Quinn and Georg Baselitz.

From 1992 until his death in 1997, Edward Quinn lived in Altendorf near Zurich with his Swiss wife Gret. She passed away in 2011.

Wikipedia english / Wikipedia deutsch / Wikipedia français

Detailed Version

Source:

DICTIONARY OF IRISH BIOGRAPHY.

Royal Irish Academy, Dublin 2009, p. 259 f. (Text by Bridget Hourican)

"Edward Quinn was born 20 February 1920 in Dublin, younger of two sons of Edward Quinn, a Guinness brewery worker and his wife Norah (née MacShane). The family lived in Dollymount, Dublin, where Edward was educated locally. On leaving school he fell into various professions before finding, by chance, his metier. After getting a certificate in metal plate work which he did not much use, he became a professional musician; his instruments were the guitar and his voice, but he learnt the contrabass on demand. This work took him to Belfast during the second world war. While sheltering in a church during a air raid, a piece of the roof fell in and the gravity of this so impressed him that he left to join the RAF and became a radio navigator. After the war he worked for Chartair (based in Tangiers). On a flight to Marseille in 1948 he met his future wife, the Zurich-born Gret Sulser. From a solid bourgeois family she marvelled at his creativity and impetuosity, saying 'I am like a Swiss watch, but with Ted - nothing was normal!' They married (17 April 1952) and had a long and loving marriage; she was his assistant and archivist. There were no children.

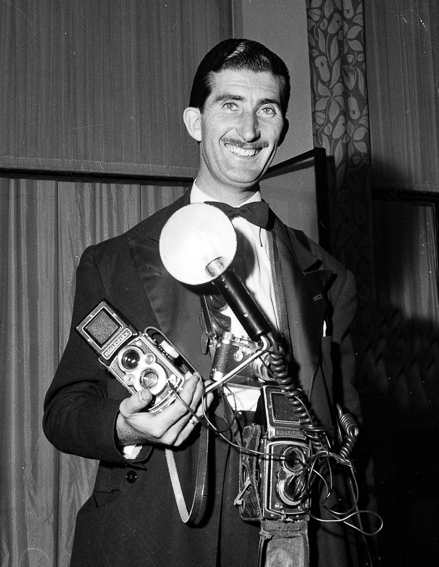

During the Berlin Airlift (Jun. 1948 - September 1949), Quinn worked for Lancashire Aircraft Corporation, flying several times daily from Wunstorf to Berlin. Gret was then working in Monaco, and in 1949 he decided to move closer to her. After returning to his old profession of musician for a few months — billed as 'Eddie Quinero, le célèbre guitariste electrique!' — he decided to try his hand at photography. The first photo he published was in the Irish Independent in 1950 - ironically since subsequently he seldom had work printed in Irish papers and was not well known in his native land. This first shot was of an Irish horse which had just won a race in Nice. His apprentice years as photographer coincided with the rise of the Côte d'Azur as a jet-set destination for film stars, millionaires and royalty, thanks largely to the fame of Brigitte Bardot and Princess Grace. Quinn worked for Paris Match and a number of agencies, principally Black Star in London and American International News Service. For these he provided snaps of celebrities such as Sugar Ray Robinson, Haile Selassie and Aristotle Onassis. He was on good terms with many of his subjects thanks to his attractive personality — besides being tall, slim and handsome he was 'charming, flirtatiously shy, friendly, rarely over-bearing' (Heller, A Côte d'Azur album, 191). His portraits from these years — collected into two books Edward Quinn, a Côte d'Azur Album (1994) and Stars, Stars, Stars... off the screen! (1996) — caught the flavour of the glamorous post-war guilt-free world, and remain fresh, elegant and informal: Edith Piaf being helped on with a shoe; Roberto Rossellini having his car serviced.

Quinn was artistic — as well as music, he studied sculpture and painting — and his ambitions went beyond the paparazzo. In 1951 he met Picasso at a ceramics exhibition. His talent, discretion and friendliness won Picasso's favour and eventually he was granted his wish to photograph the artist at work. After the first session, where Quinn took particular care to keep out of the way, he heard Picasso tell a friend: 'Lui, il ne me derange pas' (Quinn, The private Picasso, 16). They became friends and Quinn photographed Picasso for the rest of the artist's life; this resulted in four books and three films. The first book, Picasso at work (1965) was translated into six languages and widely praised for its insight into the creative process, for the self-effacement of the photographer – 'he never loses sight of the fact that his job is to tell us about Picasso and not about himself' (Tatler, 5 May 1965) — and for the photographs 'of superb character, etched in severe black and white or overflowing with marvellous colour'(Cosmopolitan, February 1965). The accolade that pleased him most came from Picasso: 'Toi tu sais faire un portrait.' The longest film (140 minutes) was Picasso, The man and his work (1974), a chronological examination of the artist's personal and creative development, using home movies and still photographs. It was praised by Picasso's widow for its exemplary honesty and creativity and was subsequently released on DVD.

The success of his work on Picasso led Quinn to collaborate with three more artists, which resulted in four more books – Max Ernst (1976); Graham Sutherland, complete graphic work, 1922-1978 (1978); Georg Baselitz (1988) and Georg Baselitz — Eine fotografische Studie (1993). He had great affinity with artists and also photographed Salvador Dali, Marc Chagall and Francis Bacon.

Though he never lived in Ireland after the early 1940s (he developed a French turn to his speech), he remained attached to the country, visiting when he could. He felt that it was his status as exile that drew him to James Joyce. Finding that the Dublin places featured in Joyce's writings were ones that he knew well.The result was James Joyce's Dublin (1974) in which photos — of bars, the races, the Liffey, street children etc — were matched with selected quotations from Joyce's works; it was Quinn's personal favourite among his books because he felt that in combining words and pictures, he had created a third sensation. It gained Samuel Beckett's praise for 'capturing the atmosphere, humour and essence of Joyce's Dublin.' Eight years later he made a 60min film, The Dublin of James Joyce and Ulysses (1982); the commentary was in French though he also released an English version.

In 1992 Quinn moved from France to Altendorf, Switzerland because he was in poor health and wished his wife to be close to her family. He died there 30 January 1997. Posthumous expositions were held in America, Britain, France and Switzerland.

His wife Gret passed away in 2011. Quinn's nephew Wolfgang Frei and his wife Ursula are taking care of the extensive portfolio.

Tatler, 5 May 1965; Cosmopolitan, Feb. 1965; “Kevin MacDonnell's Roundabout - An Irish view of Picasso” in Photography, June 1965; Edward Quinn, The private Picasso (1987); Martin Heller, ed., Edward Quinn, A Côte d'Azur album (1994); www.edwardquinn.com (accessed 18 Sep. 2005); information from Gret Quinn (widow), November 2005."