My first photos of Picasso

By Edward Quinn

My first opportunity to photograph him came in 1951 at the ceramics exhibition in Vallauris where Picasso had been living and working since 1947. Naturally I was not the only one who wanted to see Picasso on that day. Also waiting in the crowd of spectators and potters was Prince Ali Khan, another name that produced headlines. Picasso, whom I later learned was not always in a pleasant mood, came to the exhibition smiling amicably, accompanied by his friend, the poet Jacques Prévert.

Like a bishop visiting one of his parishes, he strode through the waiting crowd smiling with his head slightly bowed. When he saw potters that he knew, he stopped a few times and spoke with them. Françoise Gilot, his constant companion at that time, followed him inconspicuously, and she engaged in conversation with Prévert. At the entrance to the exhibition the reception committee was awaiting him. Nothing phased him. In the exhibition at last, Picasso, the passionate craftsman, only showed interest in the objects. He carefully examined the ceramics on display and spoke with the potters, discussing firing methods with them.

But Picasso’s own work was also on display – plates with bullfight scenes and mythological subjects, the themes with which he had begun his ceramic endeavors under the direction of Suzanne and Georges Ramié. In the mob of photographers, I followed Picasso through the exhibition. We pushed and shoved to get a good picture and I had difficulty even trying to photograph. I didn’t want to use a flash, and since the light in the exhibition hall was poor, I had to try to stand still in the crush for a longer exposure. When Picasso then began to converse with Ali Khan, it was clear to everyone that the two quite different celebrities wanted to pose for the photographers’ flashes for a moment so they would finally be left in peace.

After pictures had been taken, all the photographers rushed to their press agents. I was not under contract, so I stayed. It paid off, for just as Picasso was about to leave, his housekeeper came with his two small children, Claude and Paloma. Spontaneously, I asked Picasso if he would pose for me with his children. He was in a great mood and agreed. Afterwards, we spoke with one another for a few minutes, at which point I asked his permission to photograph him in his house. He politely refused. "We’ll see."

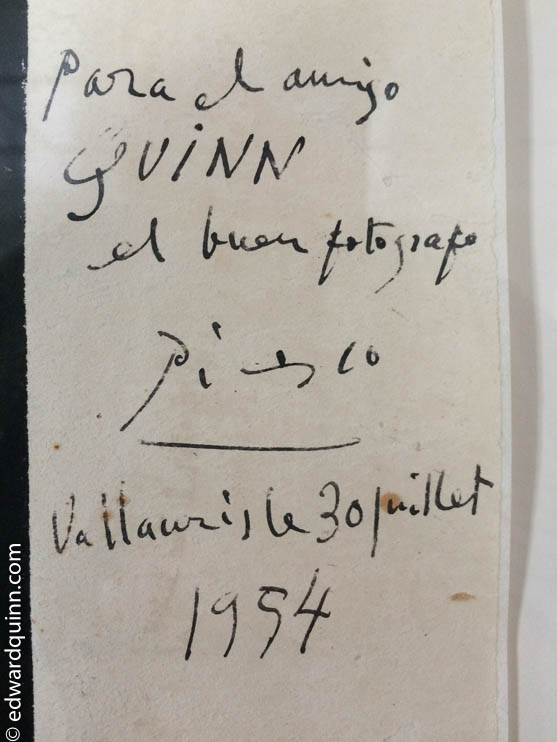

The first pictures I made of Picasso and his children pleased him so much that after a few refusals, he did finally agree to allow me to photograph him in his pottery studio in Vallauris.

First pictures at the Madoura pottery

My first appointment with Pablo Picasso in his pottery workshop was nerve–racking and difficult. I was afraid that my cautious and timid movements between the rows of stacked–up ceramics might disturb him. To me the click of my camera’s shutter seemed to resound like thunder in the atelier. Picasso, though, who was sitting beneath the statue of St. Claude, the patron saint of potters, worked with concentration, deeply engrossed and not even taking note of me.

I was very excited in this atmosphere. Picasso’s all–commanding presence, his reputation as an artist, and the fact that I was seeing him at work for the first time spurred me on to preserve those intense, quickly passing moments. I felt secure enough to experiment more than I usually did, choosing different angles, and making use of unusual lighting conditions. When the workday with Picasso came to an end, I felt very relieved and encouraged upon hearing him say to a friend, "Lui, il ne me dérange pas." (He doesn't disturb me.) Now I knew that I would be allowed to continue photographing Picasso unhindered in the future. And truthfully, from that day on, I remained one of the few photographers allowed to visit and photograph him at work and one of the very few he ever tolerated in his private domain. This gave me the unique opportunity to take Picasso’s portrait carefully over many years. In the beginning, Picasso received his visitors around midday. Later, when his illness required that he rest during the day, his guests would not arrive until late afternoon, around five or six o’clock. This added an extra problem to my work; because I rarely used a flash or floodlights, I often had very poor lighting – especially in winter.

Visiting Picasso

Whenever I was going to visit Picasso, I would carefully plan out everything I would have to do when I was with him. First, I got hold of new color film in order to be able to take pictures of his recent work; then I saw to it that all of my cameras were in excellent working order. But on the very day that I was perfectly prepared, Picasso would call it off. For this reason almost all of my visits were unforeseen and improvised. I rarely knew beforehand how Picasso would receive me, what mood he was in, or who else had just come to visit.

Whenever I went to Picasso’s, I stuffed my pockets with different rolls of film, and packed an extra lens in order to be armed for every eventuality. Experience has taught me I could only get interesting and unusual situations on film during a visit if I were prepared for everything, and did not first have to search for film in my bag or fetch a tripod from a different room.

Usually, I didn't find Picasso alone when I arrived. From 1955 on his wife Jacqueline was frequently present. Though Picasso always wanted to first engage me in conversation, I, naturally, wanted to take pictures since at that time my ambitions were those of a photographic reporter intent on getting good photographic documents. So I asked Jacqueline if I might begin as soon as it was all right. She referred me to Picasso who had observed this "clarification of authority" with amusement and smiling assent. He would have been quite amazed, had I, as a photographer, behaved otherwise. He often said a plumber must repair pipes, a painter paint, and a photographer, of course, photograph.

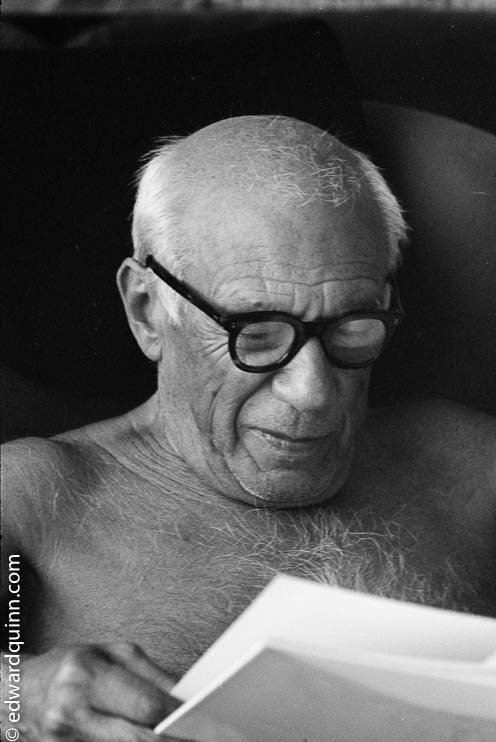

As soon as I began to photograph, he concentrated on his own expression as if he wanted to show his best side. But after a few minutes he was already so preoccupied or engrossed in conversation that he forgot about me completely. That was the exact situation I needed to take candid and believable pictures of him. To this purpose I used my camera like a pencil, taking down Picasso’s myriad activities in his familiar surroundings.

Picasso never demanded to see my pictures to, say, censor them before publication. On the other hand, he also knew that I was loyal to him insofar as I only allowed a picture to be printed if it were both a compelling photograph and a documentary. Finally, Picasso had so much trust in me, that he even allowed me into his private domain. Since I did not want to disturb this trust, a conflict naturally arose between my being a friend to Picasso and at the same time being a professional photographer who of necessity had a primary, journalistic interest in "Picasso the object". I decided without much hesitation to remain a friend of Picasso. Nevertheless, when the context of a photographic sequence demanded it, I released pictures which perhaps did not please Picasso at all. He nevertheless tolerated this because he wanted to grant me the freedom I needed for my work.

My approach to photograph Picasso

It has been said that Picasso has been photographed by many photographers who have had a totally different approach than mine. When they had an appointment with Picasso, they usually set up their lights in the corners of his atelier and placed their cameras on tripods. Picasso was very impressed by their preparations every time. When everything was ready, he sat or placed himself wherever the photographer wanted. Then the scene was lit to guarantee that particular photographer’s style. Picasso’s generous attitude, toward creative people always granted everyone complete respect in this area and kept him from mixing in. This manner of picture taking never struck me as the kind of true portraiture that would reveal his personality. It remained – even when the photographs were outstanding – stereotypical because it reflected the personality of the photographer more than the person photographed.

My ideas were less pretentious. Picasso preferred them even though the technical results were sometimes not as good. The following episode might illustrate Picasso's attitude toward photography. One of his friends was taking pictures in his atelier. An artist himself, he had altered the arrangement slightly in that he moved Picasso's slippers a little in order to organize the visual composition more advantageously. When Picasso entered the room he noticed the change immediately. "That will be an amusing photo, but not a documentary. Do you know why? Quite simply because you have placed the slippers somewhere else. I never place them that way. You did that, not I. The way an artist has his things around him is as revealing as his work."

Being alone with Picasso was easy and difficult at the same time. Easy, because we went well together; we both let each other work in peace. Difficult, insofar as I had to weigh how far I could go to obtain the documentary photos I wanted without in the end disturbing Picasso at his work. A few observations I made over the years might be helpful in rounding out Picasso’s portrait.

The most striking and fascinating facet to Pablo Picasso’s image was the ever–changing manner in which he presented himself. This part of his personality also influenced his moods and work. When Picasso was in a bad mood (this was usually caused by familial problems or unsatisfactory results in his work), he was unbearable, and nothing was all right with him. He had a remarkable simplicity in his manner and never acted like the "great genius". On the contrary, he admired the work of others and was interested in everyone. When he showed new work to friends, he was very reserved and was delighted with compliments he was clearly not anticipating.

"I don’t paint what I see, I paint what I know"

Despite his world renown and his great wealth, Picasso was insecure when in contact with people he didn’t know and often helpless with regard to the many problems of daily life. His friend Jaime Sabartés, himself no businessman, often had to advise him on business matters. Because of his fame, Picasso felt himself in a vulnerable position and always thought he was being criticized. He was proud to be a Spaniard and expected to be valued for his own sake, as an individual, and not because he was a famous, successful, and wealthy artist. He wanted to know everyone’s reason for being interested in him. Though he examined the motives, he was also susceptible to flattery. Nevertheless, he became quickly aware of its superficiality and was irritated at being the way he was. At times he could be cruel, then sensitive again, warm and sympathetic. His charm and amiability often made him irresistible, particularly to women.

Picasso liked people with character; on the other hand, he did not like it when people opposed him too strenuously. He was generous and allowed everyone their freedom as long as this did not disturb him and his work. Nevertheless, his difficult personality never actually allowed him to endure anyone for long, with the exception of his friend Sabartés and his wife Jacqueline.

Picasso's jet black, unmistakable eyes were extremely lively, often piercing, often fiery. They betrayed enthusiasm, curiosity, and alertness. He noticed everything. When he picked up a book, for example, he looked at it as if spellbound.

I was often able to observe this unique visual concentration of his, this physical attention when looking at things. Mind and body concentrated completely on what he saw. When he looked at something around him, it almost appeared as though he wanted to use his eyes in the way others would use a magnifying glass, as if he could see beneath the surface of things. With a few precise strokes he outlined all the characteristics of a face and made qualities visible which corresponded to the character of the person portrayed. That he truly perceived what he saw and could record it was Picasso’s forte. "I don’t paint what I see, I paint what I know," he once said.

My books don't, to be sure, examine Picasso’s art from a theoretical point of view; nevertheless, the work of his final years should be addressed briefly. Throughout his entire life, for over seventy years with no great interruptions, Picasso worked, always striving to become better. At the end of his life he was justified in claiming he could say something about art. In the works he painted during his final years he used a kind of shorthand, a summation of his ideas. He was well aware that he didn’t have much more time and strived, by painting and continually repainting a canvas, to further improve it. He wanted to preserve his ideas as quickly as possible, wanted to limit himself to the creative act alone, drawing upon all of his experience. The pictures produced in this vein often appear brittle, as if unfinished (particularly the series of paintings which were on display in the Palace of the Popes in Avignon). Whosoever looks at them more closely, however, discovers the richness in background color, the opulent drawing, and the radiant luminescence of the subject matter. These paintings magnificently unite a creative technique with high artistic standards.

My last visit

In January 1972 I visited Picasso in Mougins. It was my last visit. I never saw Picasso again. The following notes, which I made at that time, illustrate his lively interest and his vitality – he was, after all, 91 years old.

I was taking pictures for a book on Picasso’s ceramic work at the Madoura Pottery. Around half past one I called Picasso’s house and Jacqueline answered. She asked me to call again because Picasso was not there. Around half past four I stopped work at the pottery and went to Mougins in order to call from the telephone booths at the post office. The phone was out of order. I went into the post office but there was a long line of people waiting at the window. Irritated, I turned around and ran over to the cafe on the other side of the square to make the call. The cafe was in the process of being decorated, as I found out, because it was opening that evening. I asked if I could make a call and the owner pretended the phone was not yet hooked, "I only want to make a local call, here in Mougins," I replied angrily and insisted on being allowed to use the phone. He finally gave in and let me call. At Picasso’s house Monsieur Miguel, his secretary, answered, and I explained to him that I wanted to complete a movie on Picasso, was preparing an exhibition, and wanted to tell Picasso about it. Monsieur Miguel replied that I should indeed come right away.

At the villa he greeted me and suggested I leave my cameras in the car until it was certain I could photograph. He led me through the long hallway into the living room. There was Picasso sitting with Jacqueline and Mme. Gagarine, who had taken over the publication of the volumes of Picasso’s catalog of works in the Cahiers d’Art.

Picasso was happy at my arrival. I told him about my new movie. Suddenly, William S. Rubin, curator of the Museum of Modern Art, came into the room, a tall man with bushy, curly hair. He limped slightly and carried a beautiful walking stick. Everyone sat down, and Picasso leafed through a copy of the new volume of his catalog of works. He commented on a few pictures and was delighted to see others again in reproduction. While he was leafing through it he suddenly said, "I’m really glad I painted them."

Jacqueline offered us marrons glaces, and Picasso insisted that everyone try one, including himself. I had begun filming and taking pictures. After Picasso had looked through Mme. Gagarine’s layout, I asked him to show me his most recent work. He led me into his atelier which was adjacent to the living room. There he stood beside the “Portrait of a Woman” (1895) by the customs officer Rousseau, which was almost as tall as he himself was. The light was not good, and Picasso tried to turn the picture so it wouldn’t reflect. He took great pains and finally placed it just as I needed to photograph well. Then he brought out a few of his recent drawings, all of which had been produced in the days preceding. Represented were a group of people, a few nudes, a young girl in a realistic style.

Picasso was wearing gray and black check pants, a fawn–colored wool jacket, sweater, and vest. He was in excellent condition, very animated, very active, and his memory was as good as ever. He hurried through the house to find books or work that he wanted to show.

We sat at a large table, and Picasso drank his health tea from a very beautiful cup which, as he proudly announced, was English and from the 18th century. Jacqueline, beside him, was wearing a kimono which further emphasized that austere beauty of hers so often painted by Picasso. Like Picasso, she was also in the best of moods and full of energy for new ideas.

We talked about Picasso’s pictures in the Museum of Modern Art, the creation of “Guernica”, and the “Massacre in Korea” which he still had in his atelier. Meanwhile, he fished a reproduction of Cézanne’s “Mardi Gras” (1888) out of a mountain of papers and explained he had discovered that Cézanne must have conceived of the entire scene from an elevated position with a forward falling perspective.

Suddenly, he spotted Mr. Rubin’s beautiful walking stick, examined it with great attention, and then related that Apollinaire at one time had had a walking stick that suddenly sprouted shoots, blossomed, and became a tree. Both St. Paul and St. Francis, for example, had also had walking staffs which could blossom. Mr. Rubin was greatly amused and asked if the tale of Apollinaire’s walking stick might not be a fable. No, it was true that shoots had appeared on his stick, and it had been a sensational opportunity for Apollinaire to show the stick off everywhere. Jacqueline reported on Picasso’s dog Kabul for whom Mme. Leiris had brought along a lady friend so that the then seven–year–old fellow would no longer have to remain a bachelor. To Picasso’s great satisfaction, Kabul had joyfully given up his bachelordom when the opportunity arose, and someone had even preserved the important moment in a photograph.

I had collected a few items for Picasso since my last visit and brought them along. One of them was a small package with "secret" written on it. Picasso became very curious. Because he didn't want to cut the wrapping string, he opened it very carefully and found a puzzle game made out of little chrome tiles which were stuck onto cardboard with adhesive tape. It happened to be arranged very nicely so he left it as it was. I also had a tweed hat with a feather from Moll’s Gap near Kenmare, Ireland, and a box of incense. Picasso quickly lit one of the sticks and then another since he liked the scent which slowly drifted through the room.

In addition, I also brought him a little Indian bell for hanging on a door or window. He rang it, but finding its tone a little thin, took it, fetched a large bell with a full, somber tone, and quickly asserted that it came from the same place as the small one.

Then he began to play on a stringed instrument that looked like a harp; I think it came from Africa. Jacqueline was of the opinion, however, that he should stop, since he wasn’t as good a musician as he was a painter. With that, the conversation turned to Man Ray, whom Picasso, of course, knew quite well." Man Ray wanted to become known as a painter, not as a photographer," Picasso remarked and maintained that most photographers were jealous of painters and definitely wanted to paint as well. Apparently, they did not consider photography to be creative enough. He told about a photographer who had come to him and taken pictures of his sculpture bathed in a colored light. "He was most likely not happy with the sculptures and had thus wanted to make more of them with skillful illumination," said Picasso with amusement.

"He doesn’t want to admit to himself how old he really is," Jacqueline interjected, suggesting the end to the visit. "He still thinks he’s a young man. When he saw himself in a snapshot with 18 other people recently, he did admit, though, "I really do look like the oldest one here."

Mme. Gagarine asked whether he was really still doing sculpture. "Of course, but only at night, when I’m in bed. Then I imagine all the things I could still do and how I would do them." "Yes, he keeps me awake and describes his ideas to me," added Jacqueline.

We all left Picasso together. I shut the garden gate of Mas Notre Dame de Vie behind me. It was 10:03 P.M., January 7, 1972.

Picasso and I talked on the phone again a few days before his death. His voice sounded strange, and I had the feeling something wasn't right. He said that we had to get together again soon. These words were very important to me for they confirmed our friendship. I had not been to his house in over a year. Picasso didn’t want to be photographed anymore. He had changed. He died April 8, 1973.

In Edward Quinn. Picasso. Photographs from 1951–1972. New York 1980